In 1859 ownership of the townsite was transferred from the Board of Ordnance to the Province of Canada, and at Confederation in 1867 to the new Federal Government. The new owners made aggressive efforts to sell off the property, but it was only in the 1870s that landholders began to buy up the lots, and even then, development was slow, as ownership was consolidated into the hands of investors who were prepared to wait for the opportune time to subdivide and sell. The two chief landowners were John Henry and ‘Citizen’ John Davis (RO – abstracts for lots in plan 43586).

John Maxwell Barry Henry was born in Ireland in 1828, and joined the civil service of the Province of Canada or perhaps another province, as a collector of customs, transferring with his function to the new Federal Government in 1867. He and his wife, the former Mary Maccob, seem to have established themselves in Ottawa by the 1870s. raising a small family and moving at an early date to 478 Clarence Street. By 1891 he was was listed in the annual Civil Service Directory as Chief Collector of Customs, earning $1,200 a year – comfortable, but by no means rich.

Starting in the 1880s Henry began to buy up vacant land near his house, either from the Crown or from other owners – a reminder that in the days when financial markets were unregulated and bank deposits uninsured, many people preferred to put their savings into land and mortgages. By the 1890s Henry and Davis owned between them all of the land east of Charlotte Street and north of Clarence Street, and in 1903 Henry sold his land to Davis for $6,500 (City Directories, Canada Civil Service List, 1891, RO abstract records for plan 43586).

John and Mary Henry continued to live on Clarence Street until 1908, when he died of pneumonia and she had a stroke a few months later. The executor was Mrs G. F. Guy, a sister (whether of Henry or Mary is not known). Their son Robert Eric Henry was already an alcoholic, and died in a rooming house on James Street in 1917 at the age of 43. (City Directories, Beechwood interment records).

By contrast, “Citizen” John Davis was a prominent resident of Ottawa and a recognized leader in the Lowertown community. By his own account, Davis was born in Exeter, England, the son of a business agent for the Duke of Bedford[1]. John himself entered the Duke’s service as a coachman, and proudly remembered that he had driven Queen Victoria during one of her visits to the Duke’s estate at Woburn Abbey. This experience as a servant may be behind his later membership in the Workmen’s Association, his reputation as “friend of the working man”and prominence in the City-wide Associated Charities (Journal 1888-03-09, 1888-04-18, 1892-08-23, 1896-10-28, Census of Canada 1901)

Davis immigrated to Ottawa in 1879 with his wife and family and set up as a coachman. Within a few years he owned commercial property, ran a livery stable and sold firewood. By the 1890s he was a comfortable and substantial citizen, not rich enough to summer on the Lower St Lawrence or the coast of Maine, but with a cottage at the Cascades on the Gatineau River. He was prominent in city-wide efforts to build a public library, seek federal support for construction of the Interprovincial Bridge, and organize winter carnivals and sporting events. He hosted big civic dinners for the Mayor and Council and other worthies at his home at 494 Clarence Street. The house survived two fires, in 1892 and 1895 and still stands. (Journal 1893-10-14, 1895-04-26)

The Davis family were noted musicians and Davis himself a singer and organist who was sought out to entertain at banquets and other events. Although English in origin, an Orangeman, a member of the old St John’s Anglican Church on Sussex Street (now the site of the north wing of the Château Laurier) and a supporter of the Anglican Mission on Anglesea Square, Davis was politic enough that he was regarded by his largely Catholic and francophone neighbours as a community leader and spokesman.(Journal 1881 01-26)

He organized efforts to landscape Anglesea Square as a park, and convinced his skeptical community to support construction of special drains in Lowertown as a health measure (in this case John Henry was one of his leading opponents). As late as 1911 he was the chosen spokesman, along with Father Myrand of Ste-Anne’s Church, for the Lowertown community in their opposition to the proposed construction of an isolation hospital on Porter’s Island. (Journal 1895-08-05, 1895-12-21, 1895-12-31, 1896-10-31,1896-12-04, Citizen 1911-03-21)

He may have been a leader, but he was also strong-willed and a man of his time. In the mid-1890s he spent three years and a lot of money suing the Ottawa Electric Railway because he had been ejected from a streetcar for refusing to take his feet off the seat. About the same time he was hauled before City Council accused of digging sand out of Charlotte Street to re-sell to the City (Journal 1895-12-16, 1897-04-06, 1898-09-06).

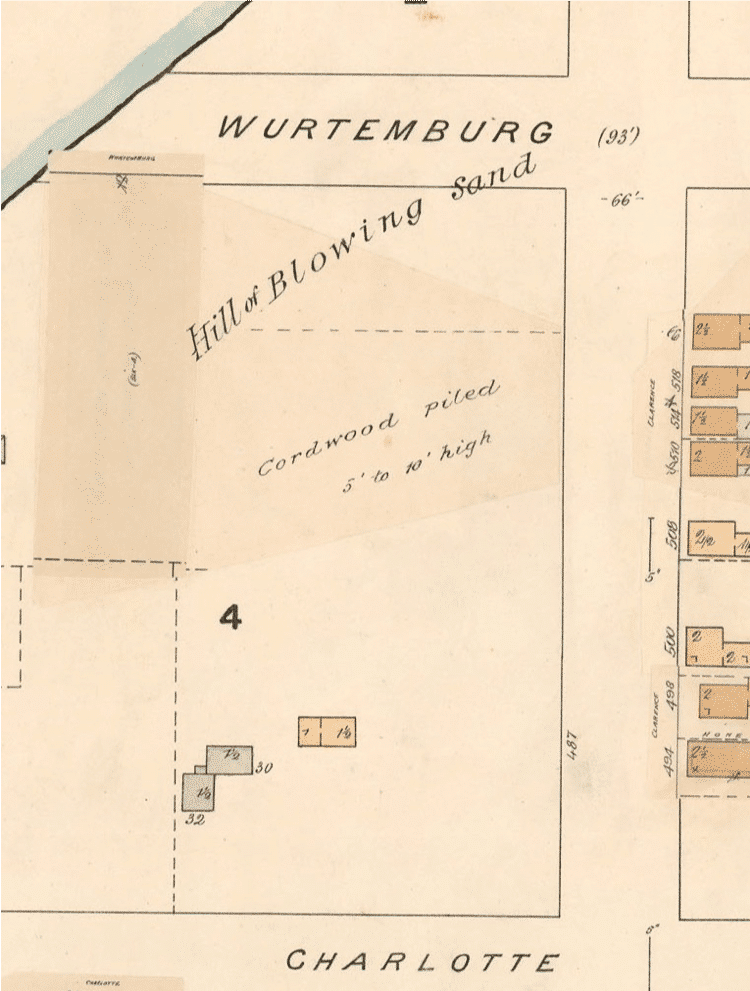

Davis used much of the land north of Clarence Street and east of Charlotte St to store carriages for his livery business and cordwood for his firewood business. He also sold sand – for filling in the lower spots in Lowertown, and for mortar for building. A 1904 article claimed that the height of the north lip of Sandy Hill (north of Clarence Street) had been lowered by 20 metres since the mining began.

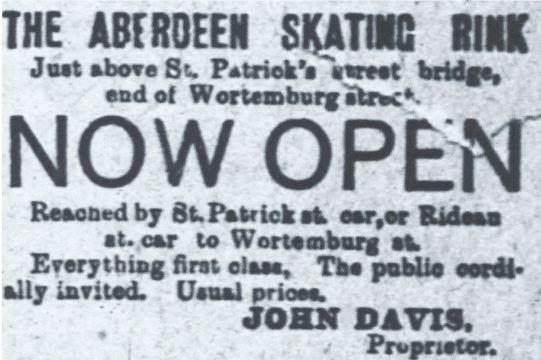

In 1894 Davis opened the first indoor swimming pool in Ottawa on the banks of the Rideau at Saint Patrick Street. A patch of paper used to update the Fire Insurance Map of 1901 suggests that it was built on Lot 1 Wurtemburg West, just south of where the street now turns, stretching back all the way to what is now Rockwood Street (see illustration on p. 7).

To support his efforts, the City gave Davis unlimited water for the pool for a flat fee of $10 a year. In those days before filters and chemicals, swimming pools had to be drained every few days and the walls scrubbed down to remove mould and algae. The building was not heated, so Davis operated it in winter as the Aberdeen Skating Rink, advertising heavily and holding periodic fancy-dress parties, accompanied by the band of Ste-Anne’s parish. When the building was destroyed by fire in February 1897 Davis did not rebuild, perhaps because other rinks and pools now existed. (Journal 1894-06-01, 1895-03-01, 1895-07-02, 1896-04-06, 1897-04-23).

With his purchase in 1903 of John Henry’s lots, Davis became sole owner of the land east of Charlotte and north of Clarence, but sold it in 1910 to the Riverview Property Limited, a syndicate of investors, for $45,000. As was common at the time, the buyers mortgaged the property back to Davis for the selling price. (RO abstracts for plan 45586)

Riverview was a local Ottawa company, but had some relationship with a number of other land companies active in other areas of Ottawa as well as Toronto and other cities. In 1910 and 1911 they extended Wurtemburg Street along the Rideau to St Patrick Street, created a new street (Rockwood Avenue – one of the other associated companies was Rockwood Realty Ltd) and divided the 13 lots of By’s original survey into 49 lots, which they proposed to sell at $1,100 to $1,500 each.

These were premium prices for the day – a suburban lot in a “better” neighbourhood like Hampton Park could be bought for $300 to $500 (Elliott 1991). To protect its investment, Riverview required buyers to build no closer than 10 feet from the street line, to lay a stone foundation, to build a house of a minimum of 2 1/2 storeys, and to face the outside with stone, brick or stucco.

Initially, sales went well, and 23 of the 49 lots had been sold by the summer of 1914. With the political crisis in Europe in July 1914 and the subsequent outbreak of war, credit froze and sales stopped completely. Riverview Property faced continuing interest payments on their no-money-down mortgage, as well as taxes and frontage charges for the unsold lots. (As was the practice until the 1950s, the City and private utilities installed services after the first houses were built, and charged at least part of the installation cost to the landowner based on the length of the street frontage of the lot). In 1918 Davis foreclosed on the mortgage and regained ownership of the remaining unsold lots. Davis reduced prices and dropped the building restrictions. With the return of peace, the return of the troops and the ensuing housing shortage, Davis managed to sell all but two of the remaining 23 lots by 1924.

Building of houses began at once, but development proceeded slowly, as many lots were bought up by local investors and well-known developers for later re-sale.

One of these developers was George Harold Lett. Born in Lanark County in 1879, he ran his business from his home in Franktown, until he moved with his family to Broadway (now Broadview) Avenue in Westboro sometime after 1937. In 1944, while walking home at night down the Richmond Road from an event at the Gospel Tabernacle, he was run down and killed by a drunken driver, leaving his widow and family a substantial estate in cash, investments and property.

Lett’s usual practice was to buy a few lots in developing neighbourhoods, build and sell houses and then move on. He is known to have built houses this way in Rideau Gardens, the Glebe, Hintonburg and Westboro. He also built houses, apartment buildings and commercial buildings under contract.

Lett first dabbled in the area in November 1919, buying lot 47 on the east side of Wurtemburg, facing the end of Clarence Street. In June 1920, however, he sold this lot to James Maclaren, who was consolidating his ownership of the land east of Wurtemburg. Lett then bought from Davis lot 27, the north-east corner of Rockwood and Clarence Streets, for $1,500. (RO Instrument 151813)

Lett immediately divided lot 27 and built two houses facing Clarence Street, using standard plan “L” (later called no. 15) from the office of the Provincial Architect. These plans were promoted as “modern and efficient’, and could be bought from the architect, who in this case may have been Charles Belfry, architect to the Ottawa Housing Commission. 78 and 80 Wurtemburg were built to the same plans, but were financed through the Commission and built by a different contractor. From this point 507 and 508 followed different histories, though the owner of 507 briefly lived in 509 in 1937 and the two houses were under common ownership for a short period in the 1970s.

Lett mortgaged the west half of the lot (507 Clarence Street) to Sarah Wilson for $4,000 at 7%. Sarah Wilson is listed in later contracts as Sarah Sinclair. She may have been the sister or wife of John Wilson, owner of lot 29 just up Rockwood Street, and they may have been connected with David Younghusband, another well-known developer who invested in the neighbourhood. Lett sold the house in 1922 to Joseph-Émile Tremblay. The financial arrangements are not clear, as the deed states simply that Tremblay was to assume the mortgage, but when the mortgage was foreclosed in 1934, Lett was still shown as having an interest (RO instrument 157515).

It has been difficult to isolate Joseph-Émile Tremblay from the many other Joseph E Tremblays in Ottawa, however it is certain that he was private secretary to Sir Lomer Gouin while Gouin was Minister of Justice (1921-1924), and likely that he was the Joseph Tremblay mentioned in later years as an administrator at the Supreme Court and the House of Commons.

In a conversation with Cathy Wenuk during the sale of the house in 2011, one of the Tremblay daughters recalled that he was an attorney, and a prominent member of either Sacre-Coeur or St Joseph’s in Sandy Hill. The Tremblays had a live-in nanny for their eight children, and on at least one occasion, were approached by the parish priest to hire a girl who had just come down from Thunder Bay to find work. To house their family and the Nanny, the Tremblays divided the high attic into six small cubicles, an arrangement that was still in place when the renovations began in 2007. (Wenuk 2014)

The Tremblays lived in the house from 1922 until 1958, first as owners and after 1934 as tenants. In 1924 Tremblay enlarged his lot by buying a strip of land 8 feet wide from the owner of lot 28 (the lot immediately to the north, which remained vacant until after 1943). Harry MacDonald, the next door neighbour at 509 did the same a few months later (RO instruments 176413, 176414).

For whatever reason, in 1931 Tremblay mortgaged this strip of land for $1,500, but three years later, in 1934, Sarah Sinclair foreclosed on the original mortgage of 1920, sold the house back to Lett and gave Lett a mortgage for 100% of the selling price at a slightly lower interest rate. The Tremblays continued to live in the house, but now as tenants.(RO instruments 213090, 213091, 213092)

In 1937 Lett sold 507 to Lorenzo Lafleur, a lawyer and commercial landlord who owned two other houses on Rockwood Street and other property nearby, and was living in 509 as a tenant at the time. Lafleur took over the mortgage with Sara Sinclair, but in 1938 added a second mortgage for $1,000 and in 1942 yet another, also for $1,000. In 1943 the City seized the 8 foot strip for non-payment of taxes and sold it to the new owners of lot 28 (still vacant at that time). Thus the odd situation arose that the lot under 509 is 8 feet deeper than the lot under 507.

In 1956 the Lafleurs remortgaged 507 to Germaine and Marguerite Roquet for $8,000 at 6%. The Roquets lived at 96 Chapel, while their father Leonide had a stone-cutting workshop at 226 St Patrick Street. Mr Lafleur died about this time, and his widow Yvonne moved into 507 in 1958 or 1959. It’s unknown whether the Tremblays chose to leave at this point, or Mrs Lafleur chose to terminate the lease. In either case, she died the following year, and her executor, her daughter, also called Yvonne, rented the house to Heiko van Essen, a salesman with Campbell Ford, then at 265 Laurier Avenue West and now at Carling and Kirkwood, and his wife Nel.

In 1961 Yvonne jr sold the house for $17,000 to Mary Chaplin, who took out a new mortgage for $7,000 with Sarah Roquet, mother of Germaine and Marguerite, and also assumed the remaining mortgage from 1934 with the heirs of Sara Sinclair. According to the City Directory, the house remained vacant, and it’s perhaps for this reason that Chaplin walked away from all her mortgages in 1963 and returned the title to Yvonne Lafleur junior. (RO instruments 413408, 456964)

Yvonne Lafleur succeeded in selling 507 again, this time to three women civil servants: Margaret and Mary Evelyn O’Connor, and Elizabeth McGovern. Margaret and Mary Evelyn may have been nieces of Harry and Mamie MacDonald (née Mary Evelyn O’Connor), owners of 509 from 1922-1941. Elizabeth died in 1968, willing her share of the house to Mary Evelyn. Mary Evelyn must also have inherited Margaret’s share, for when Mary Evelyn died in 1973, her executor sold the house for $40,000 to Norbert and Fernande Prévost, who were renting 509 at the time. As a sign of the rising inflation of those years, the Prévosts financed the purchase with a first mortgage of $25,000 at 10% and a second mortgage of $5,000 at 11% (RO instruments 4590333).

Initially the Prévosts rented out 507 to Jean-François Clausmann, a language teacher at the Public Service Commission, while they themselves continued to live in their rented house at 509. But in 1976 they moved their family to 507 and at the same time bought 509, so that for a second time houses were under the same ownership. They remortgaged 507 in 1978 for $36,000, possibly to finance renovations, as they sold in 1979 to Robert J. Wilson and Susan Stephen for $53,000. (RO instrument NS64552)

According to the City Directories, Wilson lived in the house alone until 1982, when the owners, listed as Robert Wilson and Susan Caldwell, sold to William Howard for $99,900. Howard lived in the house until 2007 when he sold it to Catherine and John Wenuk of Sandy Hill Construction.

Prospective buyers had asked John Wenuk to inspect the house with them and estimate the cost of renovations.The clients were first-time buyers and reluctant to invest in a house that needed so much work, however the Wenuks decided in their own words that “they had to save it”, and bought the house themselves. They raised the house on jacks and built a complete new foundation, added a bathroom and laundry to the main floor, redid the kitchen, added a bathroom in the attic and converted the attic to a master suite, and freshened up the other rooms, preserving the heritage features of the living and dining rooms. They put the renovated house up for sale in 2009, but were unable to sell, and so rented it to students for two years. (Wenuk 2014)

In 2011 the Wenuks were able to sell the house to the present owners, Cyriaque Meka-Mevoung and Sherry Hornung for $539,500. Ms Hornung’s mother lived nearby, and had seen the renovations in progress. She contacted her daughter (then living temporarily in Africa) and helped arrange the sale.(Wenuk 2014, RO instrument OC1235077)

In June 1922 Lett sold 509 Clarence to Henry MacDonald for $3200 plus outstanding taxes and assumption of mortgage. Harry Henry MacDonald was born on Victoria Island in 1857, son of the master of the slide that carried the timber cribs around the Chaudière Falls. Familiar with boats from childhood, he was persuaded to enter a boating race in 1873, and for the next 21 years was famous as a champion oarsman, racing for medals and cash prizes at regattas across Canada and the United States and challenging Ned Hanlan, pride of Toronto, for the title of national champion.

Like many other athletes, artists and authors of the day, MacDonald supported his rowing career with a job at the Post Office, in his case as one of that vanished species, a railway mail clerk (i.e. he sorted mail as it travelled on the train).

Tradition in the MacDonald family says that MacDonald used his prize money to pay for the house, however his racing career was long past when he and his wife Mary Evelyn (Mamie) O’Connor moved in in 1922. Their children, three sons and a daughter, were grown and scattered, eventually settling in Winnipeg, Detroit and Pittsburgh.

In 1924 MacDonald followed the lead of his neighbour Tremblay at 507 and bought an 8 foot strip from the vacant lot behind. Mamie died before 1936, and it’s possibly her death that decided MacDonald to remortgage the house in 1931 for $4,300 and move that same year to Winnipeg to be close to the son and daughter there. He died in Winnipeg in 1943, and his body was brought back to Ottawa and buried in St James cemetery in Hull (Journal, 1936-05-13, 1943-08-23)

MacDonald first rented the house to Lorenzo Lafleur, an attorney, and commercial landlord with several lots and buildings on Rockwood Street and nearby, and his wife Yvonne. When in 1937 the Lafleurs bought 507 and also moved out (but not to 507), MacDonald rented to another lawyer, Raoul Mercier, and his wife Jeanne. MacDonald finally sold 509 in 1941 to Dina Edelson, daughter of Benjamin and Alice Edelson, for $650 and assumption of the remaining mortgage. (RO instrument 234673)

Benjamin and Alice Edelson were both born in Latvia, in 1890 and 1896 respectively, and married in the Bronx in 1912. By the time they moved into 509 five of their seven children had left home, only daughters Dina (then about 26 years old) and Lilian remaining. Benjamin and Alice were living in Montreal when they came to Ottawa for a visit in 1920 and decided to move. Benjamin had trained as a watchmaker, and so they opened a jewellery store in the old Daly Building at 588 Sussex Street, later at 24 Rideau Street next to the Union Station (now covered by the intersection of Mackenzie, Rideau and Col By Drive). The family continues to operate the business at 379 Dalhousie Street. (Mindspring.com, City Directories)

The family became the focus of public attention in 1931 when Benjamin was accused of murdering another jeweller, Jack Horovitz, who, it was revealed, had been carrying on an affair with Alice for several years. After a sensational trial, Benjamin was acquitted in 1932 and the Edelsons resumed their life. Monda Halpern, a professor at Western University published in 2015 a book Alice in Shanehland, that uses the case to explore the prejudices of the day. The Edelsons are also a reminder that much of Ottawa’s Jewish community clustered in the eastern parts of Lowertown and Sandy Hill, close to the Beth Shalom synagogue on King Edward Avenue. (The original building is now the francophone Seventh-Day Adventist church, while the interior fittings have been moved to a new synagogue in Craig Henry).

The Edelsons rolled over their mortgages for $3,000 in 1942, and in 1950 sold 509 to Blanche Mayneux for $10,500. She sold the vacant house the following year to Rodolphe and Lucille Lavictoire for $14,400. Rodolphe worked as a shipper at Brading’s Brewery, the original property from which E.P. Taylor built his career as financier and industrialist.

As part of his merger of Bradings with another Ottawa brewery, Taylor had already moved Bradings from its original location on Wellington Street facing the end of Sparks Street (when the two streets still met) to a new building at 840 Wellington on the southwest corner of Preston Street (today Albert and Preston Streets). Both the brewery and its warehouse across Wellington Street are long gone, but they pop into the news periodically because of legends that when the warehouse was demolished, the plant’s railway locomotive was simply sealed up in the tunnel that led from the sidings in the warehouse basement to nearby rail yards. This tunnel is often confused in accounts with the well-attested tunnel that led under Wellington Street from the brewery to the warehouse.

In 1970 the Lavictoires sold to Royal Lavoie, a sheet-metal worker at Canadian Comstock Corporation, a specialist contractor for industrial installations, for $23,500. Royal and his wife Fernande lived at 509 until 1976, when they sold the house for $45,000 to Norbert and Fernande Prévost, owner-residents of 507. This was the only time the two houses shared a common owner. The Prévosts sold that same year for $54,900 to the present owners and residents, William E Langdon, then Vice-principal of Fielding Drive Public School, and his wife Pamela.

Davis gave his year of birth at various times as 1834 and 1848: the latter date fits better with anecdotes of his early life and date of immigration.