Two landowners, the civil servant John Henry and businessman ‘Citizen’ John Davis, gradually consolidated all the lots in the area east of Charlotte Street and north of Clarence Street until in 1903 Henry sold his portion to Davis for $6,500 (RO – abstracts for lots in plan 43586). Henry was strictly an investor, renting out his land, but Davis had a much greater influence on the face of the neighbourhood.

Davis was born in Exeter, England, probably around 1848, the son of a business agent for the Duke of Bedford. John himself entered the Duke’s service as a coachman, and proudly remembered that he had driven Queen Victoria during one of her visits to the Duke’s estate at Woburn Abbey. This experience as a servant may be behind his later membership in the Workmen’s Association, his reputation as “friend of the working man”and prominence in the City-wide Associated Charities (Journal 1888-03-09, 1888-04-18, 1892-08-23, 1896-10-28) Davis immigrated to Ottawa in 1879 with his wife and family and set up as a coachman. Within a few years he was a substantial citizen, hosting civic dinners at his home at 494 Clarence Street. A recognized community leader in Lowertown, he organized efforts to landscape Anglesea Square as a public park, and convinced his neighbours to support the construction of drains to carry away the runoff from Sandy Hill. John Henry was one of his leading opponents.

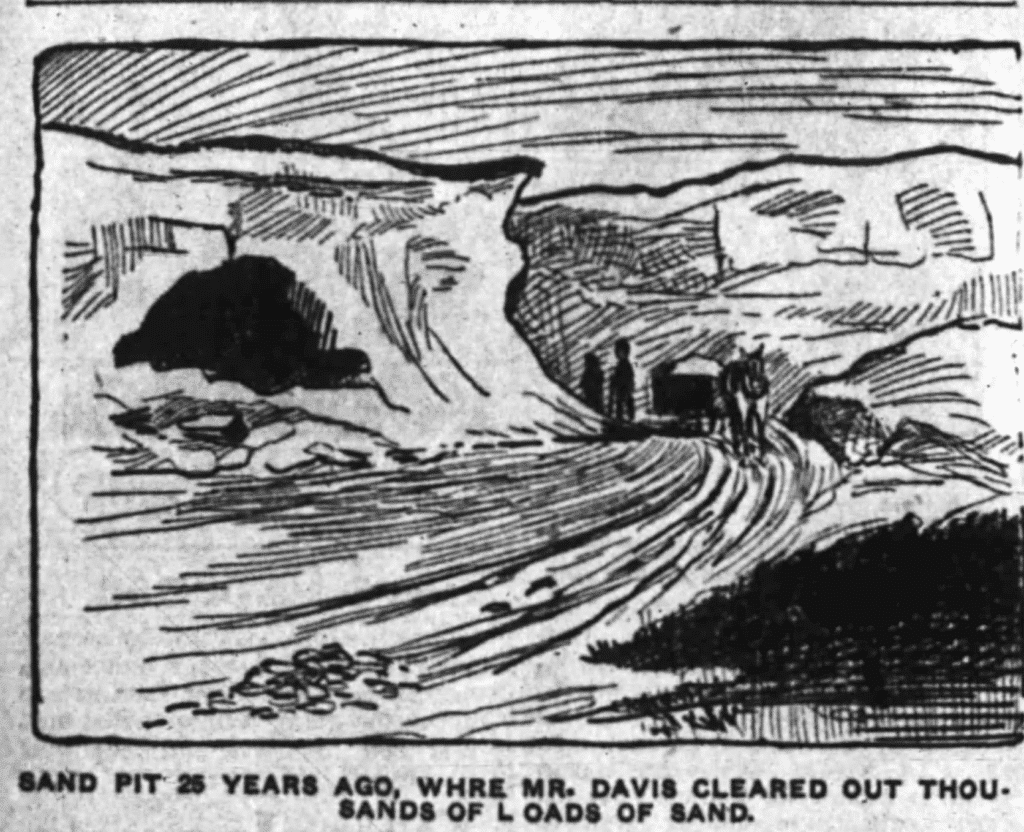

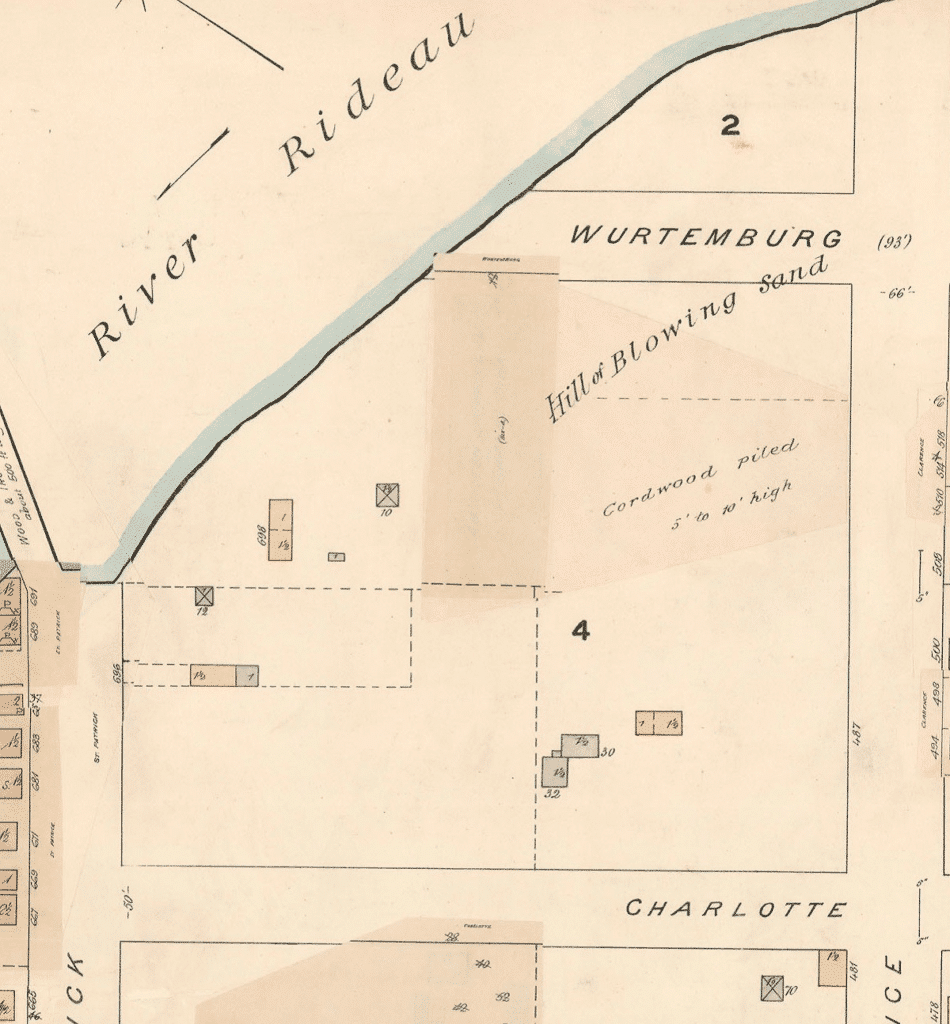

As late as 1911, Davis was one of the spokesmen (along with Father Myrand of Sainte-Anne’s Church) when the Lowertown community lobbied against construction of an isolation hospital on Porter’s Island (Journal 1895-08-05, 1895-12-21, 1895-12-31, 1896-10-31,1896-12-04, Citizen 1911-03-21) Many old accounts emphasize the height of the north end of Sandy Hill: a map of 1888 describes the land north of Clarence as a ‘hill of blowing sand’. Davis dug out masses of sand: some was used to fill in the swampy land immediately to the west, much of it used in mortar for the stone and brick commercial buildings rising in the growing city. It’s a guess how far the hill was dug down: thinking back as a boy, alderman Desjardins was sure the hill was at least 60 metres high; in 1904 Davis himself estimated that he had lowered the hill by 20 metres. One can only suggest that the hill was originally much higher and steeper, and that Davis probably stopped digging when the hill reached a gentle slope safe for construction.(Journal 1898-09-06, 1904, Citizen 1889-07-26, 1926-12-31)

Davis also used the land to stack and dry firewood, which had become his major business, while he and others pastured their horses and stored their wagons on the unused streets. The area, vacant, yet close to town, was also used to dump garbage and sewage, and sheltered the drifters and homeless at the margins of Victorian society. Eventually (1903) the City fenced off the stub end of Wurtemburg Street north of Clarence to discourage vagrants.attracted drifters and the homeless. Davis made another use of his land: in 1892 he opened the Aberdeen Baths on Wurtemburg Street north of Clarence, the first indoor swimming pool in Ottawa. There was no heating, so it ran as a skating rink in winter until it burnt down in February 1895.

With his purchase in 1903 of John Henry’s lots, Davis became sole owner of the land east of Charlotte and north of Clarence. A newspaper story of 1908 noted that Davis was still doing a thriving business (not specified) on the land, but intended to keep it for future sale as residential lots. That day came in 1910, when he sold the land to Riverview Property Limited, a syndicate of investors, for $45,000. As was common at the time, the buyers mortgaged the property back to Davis for the full selling price. (RO abstracts for plan 45586, Journal 1908-03-21)

The ownership of Riverview Property Limited is uncertain: Davis himself may well have been one of the shareholders. However, it was associated with a number of companies promoting development in other parts of Ottawa, possibly through interlocking ownership. One of the associated companies was Rockwood Realty Limited, whose “provisional directors” were listed in 1911 as Cleophas Perron (a hotel keeper at 65 Clarence Street), Joseph-Albert Faulkner (owner of a clothing and dry-goods store on Dalhousie Street) and Dr. Rodolphe Chevrier (a parishioner at Sainte-Anne).

the drift towards the First World War stopped all sales. (Eventually, in 1918, Davis foreclosed and regained ownership of the remaining unsold lots).

Ovila Blais builds 18-20 Rockwood for John Harvey Cottle, 1911/1912 Josephine Prud’homme and her husband Ovila Blais, a contractor, were the first buyers of lots on Rockwood Street, purchasing two lots (20 and 21) in 1911 for $1,350 each.

As background a developer of the day was expected to do no more than mark out lots on the ground (a few might do more, but that was unusual). Infrastructure and services were installed by the municipality or private utility companies once buyers had begun to build houses. A buyer who wanted a new house found a suitable lot, then hired a contractor (and perhaps an architect) to design and build the house. As an alternative, a contractor would buy one or more lots in growing areas on credit, then offer the buyer a package deal: a lot, a choice of designs and construction of the house to suit, the buyer taking over the mortgage arranged by the builder. This practice meant the contractor did not have to raise financing for the house until the sale was guaranteed, an important consideration for small builders with limited capital. Sometimes the builder might actually choose the design and begin construction before the house was sold, but this was much riskier. There is not much to be found about Ovila and Josephine Blais, but from the City Directories, it appears that he was a carpenter who had raised enough money to go into business as a builder. As a young couple without children, they were able to camp out in the houses he was building, moving as each was finished and the buyer moved in.

The 1912 City Directory (information gathered in 1911) records the Blais as living at 20 Rockwood Street, the only residents on the whole street. That same year (March 1912) they sold lot 21 (18-20 Rockwood) to John Cottle Harvey for $1,500, subject to mortgage and building restrictions (as laid down in the original Riverside Property Sale). As no mortgage was ever registered, the actual price is not clear: $1,500 cash and assumption of an existing mortgage for $1,350 (or perhaps more) could be a reasonable (if low) estimate, but then construction of the house was often covered by a separate contract.

The City Directory for 1913 records Harvey living at no 18 and the Blais living in a new house at no 22 (on lot 20). Whether the Blais built no 22 completely on spec, or an expected sale fell through, they were unable to maintain control of no 22, and surrendered title to Thomas J Nellis or Nelles for $1: Nellis was Ottawa solicitor for the Quebec Bank (merged with the Royal Bank in 1917), which presumably held the mortgage on the property. Blais’ dreams of success were shattered, at least temporarily: by 1918 he is listed as a journeyman carpenter working for a builder in Hull.

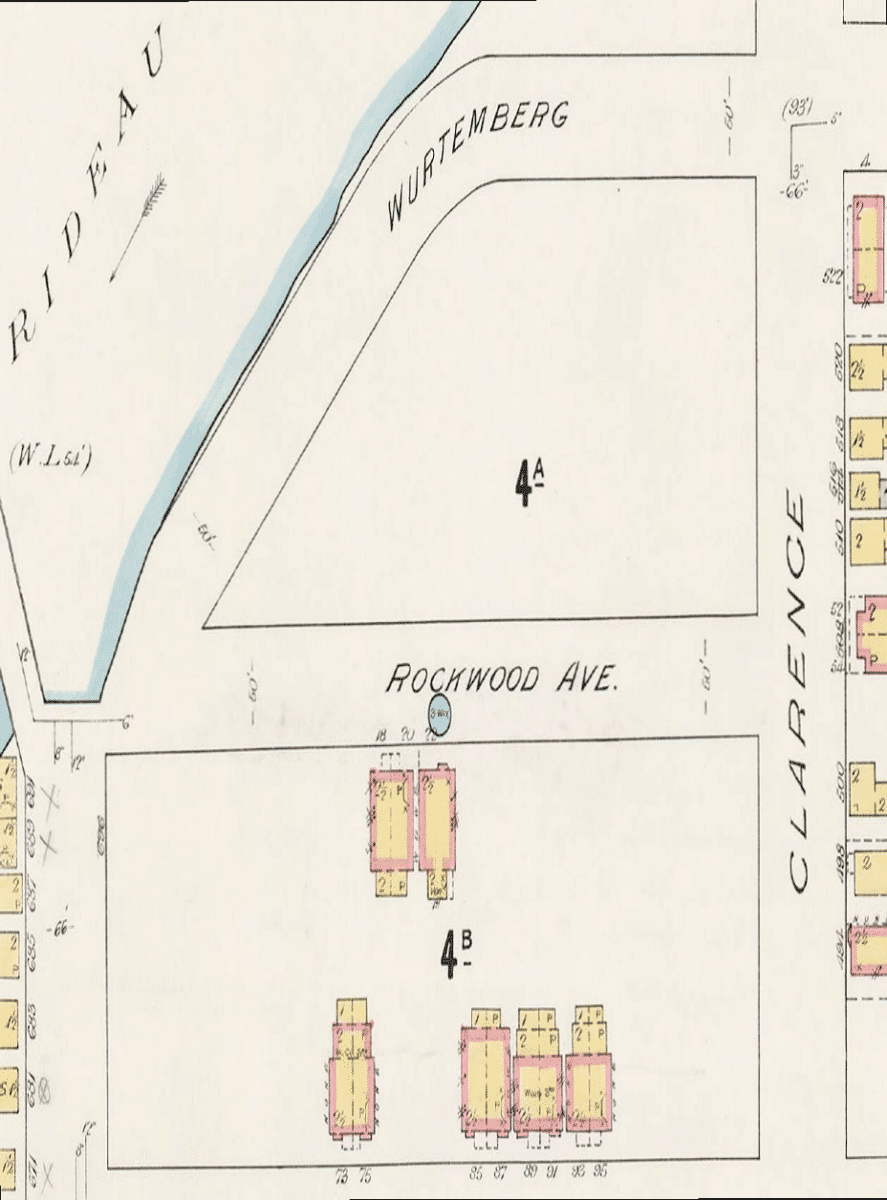

Although the romantic towers of 18-20 Rockwood suggest that it must be must be far older than records suggest, much of that sensation comes from the fact that all the surrounding houses, except no 22, were built after the Great War, in 1921-1925 or later, at a time when governments and builders were promoting “modern” and “efficient” designs reflecting research into the design of houses that were “healthy” and could be maintained and operated without paid or unpaid domestic help. 18-20 would look quite at home with other houses built for the somewhat extravagant taste of the Edwardian era. No 22, although contemporary 1 with 18-20 represents a simpler style of hip-roofed house common across the City. Still, it is worth examining whether the house might in fact be older than 1912 (e.g. was built before Rockwood Street was laid out). We can start with the Fire Insurance Map of 1888, revised to 1901.This shows the area east of Charlotte Street as vacant except for a few scattered frame buildings (labelled 487 Clarence Street and 30-32 Charlotte Street). It also shows a fence between lots 58 and “I” of the 1859 survey running across the middle of the future lot 21, i.e. right through the site of 18-20. Given the neighbourhood, it would also be unusual to build a fancy house, especially a pair of semi-detached houses, in the middle of a lot subject to flooding, difficult access to the street, and no access to public services. A new fire insurance map was prepared in 1901, revised in 1912 and again in 1915 (rather than draw new maps each time, for as long as possible the old maps were

simply updated by drawing in new buildings and covering changes and demolitions with darker strips of paper, so that changes could be tracked). The 1912/15 revision is the first to show 18-20 Rockwood, along with 22 Rockwood. This is consistent with the information from the Registry Office, which suggests that the other houses were built starting in 1921.

The summary Assessment Roll for By Ward of 1911 (based on information from 1910) is blunt: Rockwood Street is listed as empty of houses2. Similarly, the City Directory has no entry for Rockwood Street until 1912, when it lists the Blais as the only residents, at no 20.

Thus the accumulated evidence strongly suggests that 18-20 Rockwood was built in 1911-1912 by Ovila Blais for John Cottle Harvey, likely to a design chosen by Harvey to reflect his arrival as an influential member of the Ottawa business community.

John Cottle Harvey had worked his way up in the hardware business, starting as a clerk with Thomas Birkett on Spark Street and progressing as manager with Thomas Shore at 115 Rideau Street (corner of William), and eventually as senior partner in Grey and Harvey, who took over and expanded Shore’s business, with “sample rooms” at 67- 69 William Street at the corner of George.

After marrying Mary Pearce in 1901, the Harveys had lived with his in-laws at 15 Elgin Street, before moving to 244 Besserer Street (at the corner of Cumberland) and finally to 18 Rockwood Street in the spring of 1912. It is perhaps a sign of native caution that an established merchant and member of a socially prominent church (All Saints Sandy Hill on Laurier Avenue), chose to build a semi-detached house, with one half rented as a revenue property, but the whole designed in a solid, extravagant style to demonstrate that he had arrived. Similarly, the Harveys summered in the Gatineau, usually with their in-laws, usually at summer hotels in places like Kirk’s Ferry, rather than buying a summer place of their own.

The Harveys had begun investing in lots in Sandy Hill even before they moved to Rockwood Street. In 1920-21 they added the lot immediately north of 18-20 to their land and briefly held the next lot after that, selling in 1923 for $1,200. The street began to build up in the 1920s, but some lots remained vacant into the 1950s. Harvey continued to prosper, and in 1928 he moved to a much grander house at 324 Laurier Avenue East (now divided into flats), renting out no 18 to Mrs Mary Ward, a widow, and her three grown children. However, in a pattern common in Ottawa at the time, in 1937 or 1938, William Pearse or Pierce, nephew and heir to John Harvey moved into no. 18 with his wife Mabel, and inherited the house on Harvey’s death in 1941. The Pearses sold off the extra lot in 1955 for $3,500, and continued to live in the house until 1966, 54 years after William’s uncle had bought it.