Perhaps you wonder about when the home was built, who built it, and the lives of the many people who’ve lived there.

If so, this is the perfect project for you!

Together we’ll delve into the lives of some remarkable Ottawa homes, thanks to David LaFranchise and Marc Lowell of House History Ottawa. Their in depth research on Ottawa’s many historical homes opens the doors to this city’s fascinating past.

House History Ottawa has been chronicling the histories of Ottawa’s old homes for decades. In this exhibit, we share a slice of the wealth of information that they have dug up over the years. Focusing on five homes in Ottawa’s Lower Town, we’ll explore a variety of residences, not only structurally but also in each home’s unique history.

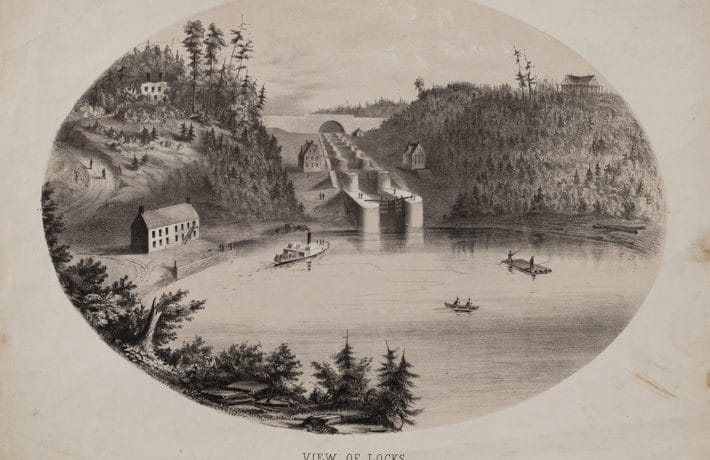

When Lieutenant-Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers arrived at the Chaudière Falls in 1826 to begin construction of the Rideau Canal, many people were convinced that a settlement at the portage around the Chaudière would become an important commercial centre, controlling the growing trade of both the Ottawa River and the Rideau Canal. Promoters had already laid out townsites on both sides of the Ottawa River at the Falls, while the government of Upper Canada had, in 1823, bought the high land south of the river from its absentee owner (lot B in Concession B and lots B and C in Concession C, Rideau Front of Nepean Township, roughly the area bounded by the Ottawa and Rideau Rivers, and today’s Bronson Avenue, Wellington Street, Rideau Street and Cathcart Street) (Elliot 1991 p 15ff).

By took ownership of the government land for the Board of Ordnance, the arm of the British Government in charge of military installations, chose a site for a fortress and laid out a townsite around it, part on the higher ground west of the route of the Canal (Uppertown) but the commercial core on the lower ground east of the Canal (Lowertown). The Board kept ownership of the land, but leased out individual building lots.

By planned the area east of King Street (today’s King Edward Avenue) as a neighbourhood for senior military officers and wealthy merchants. Large lots faced streets and squares with elegant names, including Clarence for the King’s brother William, Duke of Clarence (later King William IV); Charlotte, for the King’s daughter Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales; Wurtemburg, for the King’s eldest sister Charlotte, Queen of Wurtemburg; and Parry and Franklin for Sir William Parry and Sir John Franklin, admirals and arctic explorers. At the time, the search for the Northwest Passage was a priority for the Royal Navy, and arctic explorers were celebrities.

When the City moved in the 1870s to number houses and clear up duplicate street names in preparation for house-to-house mail delivery, Clarence, Parry and Franklin Streets, more or less in a line, were consolidated as Clarence. Heney Street, formerly just a lane along the edge of the cemeteries, was also named for John Heney, landowner, businessman and alderman, about this time.

Prosperity and growth by-passed nascent Bytown: the proposed fortress was cancelled, and the commercial importance of the Ottawa River was already in decline when By arrived. Ottawa began to grow quickly in the 1850s, however, when a free trade agreement encouraged the export of softwood lumber to the United States, and the Provincial government voted to move the capital to Ottawa (1858, although the actual move from Quebec City did not take place until 1865).

Even so, the streets in the eastern part of Lowertown remained empty. The public blamed legal problems over the Board of Ordnance’s title to the property and the confused administration of its leases. But even after 1859, when the Board transferred ownership of the Canal and the townsite to the Province of Canada and the Province moved quickly to settle the leases and put the lots up for sale, there were few takers.

In an era when walking was the only means of transport for all but the farmer and the very rich, and roads were very poor, Lowertown East was just too far away from the new mills at the Chaudière and the Rideau Falls. Further, low areas were impassable hemlock swamp, cut by streams draining the hills, while the higher pine-clad hills turned to loose blowing sand as soon as the trees were felled. Both the Board and the Province were reduced to letting the land in large 2-3 acre lots to farmers and market gardeners, and to looking the other way at squatters who simply harvested the timber and occupied the land without any legal title.

Most of the lots remained unsold when the Federal government assumed ownership at Confederation. Bytown did not become the military and commercial centre that By anticipated. When the town finally began to grow in the 1850s, both rich and poor chose to live near the new mills at the Chaudière and the Rideau Falls, or on the high ground to the south and west. By contrast the lower parts of the east end of Lowertown remained impassible hemlock swamp cut by streams, while the surrounding pine-clad hills quickly turned to loose blowing sand once the trees were felled. Tenant farmers or squatters grew vegetables, cut the timber or quarried sand (Elliott 1991, p 93).

To learn more about other Ottawa neighbourhoods and their many residences, you can visit House History Ottawa’s website.

David LaFranchise and Marc Lowell can be reached at [email protected]

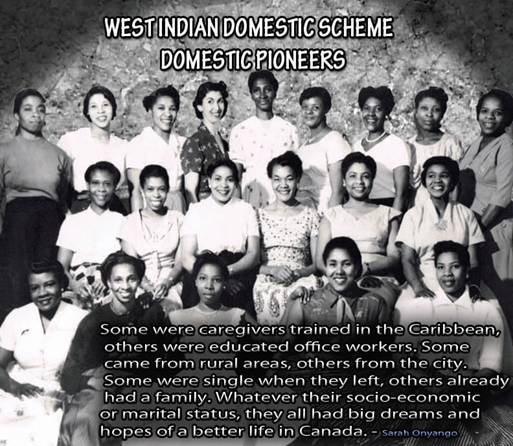

The documentary The West Indian Domestic Scheme Domestic Pioneeers is an oral and community history project started in 2010 by the Ottawa-based non-profit organizations Jaku Konbit and Black History Ottawa. The documentary, directed by Garmamie Sideau, sought to show the contributions of Caribbean women to the National Capital Region and to Canadian heritage. Over the course of two years, Sideau interviewed numerous women who had moved from the Caribbean to Canada to work as domestic workers in the 1950s. The interviews reveal these women’s hardships, perseverance and the immense contributions they made to Canadian culture, and to the raising Canadian citizens.

Officially called the West Indian Domestic Scheme, the 1955 Canadian policy responded to pressure to allow more Caribbean immigrants into the country, so long as they were women willing to work in the domestic field. After working for one year as domestics, they were permitted to take up employment of their choosing and bring family members into the country. This scheme followed decades of racist policies that greatly restricted non-White immigration to Canada, including an official 1953 statement justifying such discrimination on the grounds that West Indian immigrants could not stand Canada’s harsh winters.

Under the Domestic Scheme, around three thousand West Indian women moved to Canada. To be accepted into the scheme, they were required to meet four criteria: they had to be between the ages of 18 and 35 and unmarried, have attained at least an 8th grade education, have passed a medical examination, and been interviewed by Canada immigration. Only successful applicants were authorized to migrate to Canada, and so many of them left families behind when they accepted jobs up North. Of the accepted women, the vast majority moved to Montreal or Toronto, with a number also settling in nearby cities such as Ottawa. This documentary focuses on the women who settled in Ottawa, their experiences and how their lives shaped the Canadian capital for the better.

The sharing of this history was made possible by Jaku Konbit and Black History Ottawa.

If you are interested in watching the entire documentary, it is available for purchase through this link.

Come face-to-face with notable Jewish Ottawans and learn more about these figures, their lives, and contributions to Canada’s public service and political landscape. Whether they were born in Ottawa or came to the city later in life, these individuals led storied lives and are part of the fabric of our community and our country.

This is a virtual representation of an exhibition originally designed to take up physical space. In the gallery space, the arrangement of portraits mimicked the style of a family photo wall, and like the pictures on our walls at home, they invited us to reflect – they remind us of lives lived with purpose and meaning and they call for us to focus on the very things that make us human.

In this visual representation, we invite you to flip through the photos as if you were going through a family photo album, allowing you to enjoy the portraits in the spirit that the exhibition initially intended.

To learn more about each person photographed in the gallery, peruse the side-menu to open individual biographies featuring images from the Jewish Bulletin.

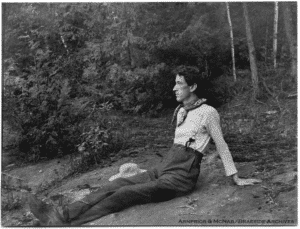

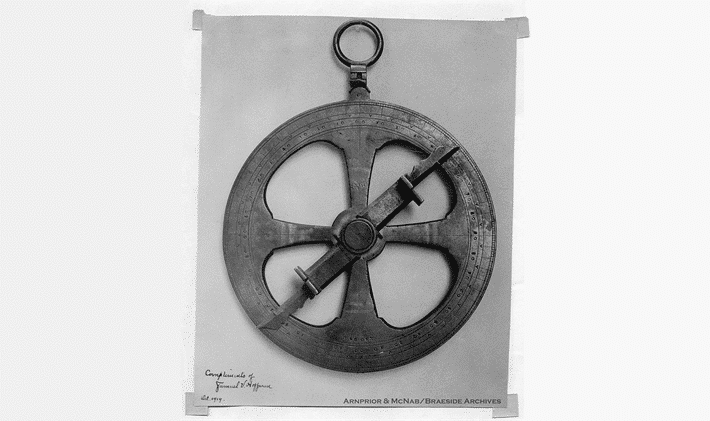

Included in this set of images are photos from one of Macnamara’s scrapbooks. The map of Champlain’s route is not part of the scrapbook; however it is included in this display to show Macnamara’s interest in Champlain’s precise travels and his knowledge of the Ottawa Valley. Also the image of Macnamara himself is from another scrapbook and is included to provide a short biography. The last three images are in the order that Macnamara included them in his scrap book. The first of these three puts the area around the site into context, the next images move incrementally closer showing further details of where the astrolabe was found.

Macnamara’s photos have been scanned from glass plate negatives. Around the side of each photo the emulsion’s edge is still visible and is a reminder of the medium used by Macnamara.

-Ryan Tobalt (AMBA 2013 Summer Student)

Charles Macnamara lived in Arnprior from 1881 to 1944, and worked as secretary treasurer for the McLachlin Bros. At one point in Macnamara’s life he became quite interested in the 16th century explorer and soldier, Samuel de Champlain. He conducted comprehensive research using his own correspondence with others, his interviews and knowledge of the Ottawa Valley to complete articles, such as “Champlain as a Naturalist” and “Champlain’s Astrolabe”.

It is interesting that in the years following Macnamara’s Champlain articles, the erection of a monument to Champlain on Chats Lake was discussed by Arnprior council. This is documented in the Arnprior Chronicle of January 13, 1928.

The following is an excerpt taken from Laurie Dougherty’s “Charles Macnamara – A Retrospective”

“Charles Macnamara worked as secretary-treasurer for the McLachlin Bros. Lumber Company for 46 years. From 1908 to 1917, Charles Macnamara was involved with the pictorial movement in photography. During this period he took many award winning photographs which have been published in multiple articles and photographic journals. Charles Macnamara was also an amateur entomologist, historian and field naturalist who contributed articles to various publications throughout his lifetime.

During his time in Arnprior, Macnamara became extremely interested in Champlain’s Voyage through the Ottawa valley. Correspondence shows that he took a great deal of time and effort preparing articles, such as “Champlain’s Astrolabe” and “Champlain as a Naturalist”. It was in 1919 that E.D Lee and Charles Macnamara made their way to the site where the astrolabe was found on green lake. Thanks to Macnamara’s detailed nature, there are today photographs of what they saw on their excursion and a precise account from E.D Lee himself.”

The Charles Macnamara collection is a wonderful piece of Ottawa Valley heritage and is preserved at the Arnprior & McNab/Braeside Archives.

Champlain’s Astrolabe is an online exhibit curated by Ryan Tolbalt, a 2013 Summer Student with The Arnprior & McNab/Braeside Archives. The photos curated for the exhibit come from the Charles Macnamara collection and tells the story of Macnamara’s interest in Samuel de Champlain as a naturalist in the Ottawa Valley.

This adaptation of Tolbalt’s exhibit comes in two parts. The first page shares a short history on Macnamara’s life. The second page provides a selection of images found in one of his scrapbooks, and his own commentary which accompanied them.

If you are interested in learning more about the Arnprior Archives or the Charles Macnamara collection for yourself, you can find them online at AMBA Archives .